Bankside Yards & 50 Fenchurch St: will new Rights of Light disputes amend 200 years of case law?

Project leads

Contacts

Richard Nosworthy

Richard Nosworthy heads up the Neighbourly Matters team, which comprises of Daylight, Sunlight, Rights of Light Consultancy, Party Wall advice, Boundary Disputes and Oversailing Licence services. He is a highly dedicated and conscientious advisor, who has a proven track record for delivering expert strategic Rights of Light/Planning Daylight & Sunlight advice for developers, financial institutions and government bodies in some of the UK’s most challenging locations.

Richard works on daylight, sunlight and rights of light issues for major mixed-use developments, large residential developments and a variety of other projects for top UK investors. He supports overall planning strategies by delivering the largest possible massing whilst minimising impacts to neighbouring properties.

Notable projects include large mixed-use residential schemes such as the redevelopment of former Honey Monster Factory (Quayside Quarter) providing 1,997 residential units over nine blocks, up to 29 storeys. Richard also advises central Local Authorities, such as Camden and Tower Hamlets, in relation to their own redevelopment schemes and providing advice on third party developments.

Rights of light is an aspect of real estate ownership and development based mainly on over 200 years of case law history. There are fewer than 40 notable cases of which 10 are commonly referenced by experts.

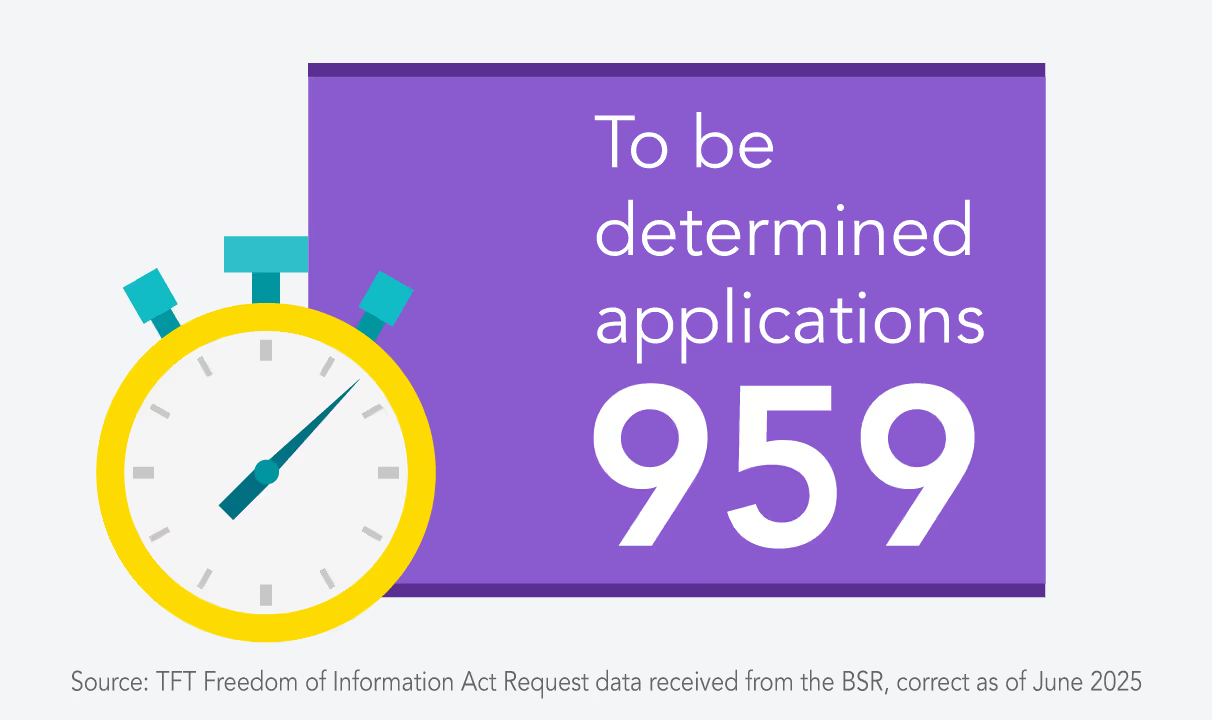

In recent months, two prominent rights of light disputes have arisen and are due to be determined by UK courts this year. The outcome of each case may fundamentally affect how we understand and resolve similar disputes for many years to come.

But what are the cases, and what could they mean for the rights of developers and neighbouring property owners?

What are the Bankside Yards and 50 Fenchurch St disputes?

The first case relates to Ludgate House Limited’s Arbor tower, part of the Bankside Yards development in London. The tower potentially faces an injunction which may require the owners to demolish part of the building which impacts a neighbouring property, as well as restricting further towers within the development. This has now been heard by the High Court and we await a decision later this year.

Meanwhile, the owner of the Willis Building is pursuing a legal right of light claim against AXA IM Alts, in relation to its 50 Fenchurch Street development. The two sites are in the City of London, a crowded and complex landscape for considering rights of light which usually means that disputes are settled by compensation settlements.

This matter has yet to be heard, and a decision is expected to follow sometime after the determination for Bankside Yards.

Why are Rights of Light disputes on the rise?

While two such cases are rare in the history of rights of light, we may see a rise in similar legal actions due to a more congested skyline, particularly as more high-rise developments reduce overall ‘baseline’ daylight levels in city centre locations, resulting in greater sensitively to daylight reductions. This will be exacerbated by developers designing larger developments as a means of offsetting higher construction costs.

Developers are increasingly putting themselves at risk by relying on reactive right of light insurance policies to cover settlement claims against them – and seen as ‘poor conduct’ by the courts – rather than managing development injunction risks by design or undertaking proactive negotiations with neighbours.

Invariably these policies don’t cover injunctions. As a result, new companies are being created specifically to pursue rights of light claims on behalf of neighbouring legal owners and usually demanding excessive sums in compensation.

Could we see a new Rights of Light methodology?

These two cases – like many before them – rely on the ‘Waldram’ methodology for measuring light levels.

Waldram has been in place for over 100 years and assesses direct daylight at table-top ‘working plane’ height only.

Today, we have sophisticated computer-based 3D models improving the accuracy of these assessments, but there are also newer climate-based methods which might be considered by the courts in determining the two cases I have previously referenced. These new methods take account of direct daylight and reflected light from both internal and external spaces. By including these further light sources, greater light retention may be calculated and as a result, claimants could find it harder to claim a legal interference to their right to light.

As a result, we could see more cases resolved by damages rather than injunction, potentially unlocking larger developments thanks to a lower risk of delays and costs.

This will be an enticing prospect for developers. However, it also raises several new questions.

If the climate-based methodology is to be considered, how should it be applied? Results can vary based on the low reflectance of a masonry building in one scenario versus highly reflective glass cladding in another. Accounting for these variables over time will be difficult and could significantly benefit either developers or neighbours depending on the specifics.

I would expect this to be an ongoing point of contention until a sufficient body of case law provides further guidance from the courts.

If the Waldram approach is retained, the developers in these cases will hope for a decision that no legal interference has occurred or that damages in lieu of injunction will be sufficient remedy.

Can developers avoid a Rights of Light injunction?

Injunction has always been the primary legal remedy for material interference with a right to light. Should the courts determine a mandatory injunction, the offending part of Arbor could be required to be removed. This will solidify a decision by the Supreme Court in the case of Coventry v Lawrence [2014], highlighting the risk developers take on by proceeding with development without resolving rights of light claims and relying – instead – on reactive insurance policies.

The owners of the 50 Fenchurch Street development may have a different sort of ‘get out’ option: it is possible that the City of London will use its statutory powers under Section 203 of the Housing and Planning Act 2016 to override easements to light. Since Section 237 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 was supplanted by this Act, it was hoped that the benefit of these expanded powers – which can help deliver the ever-widening need for large scale developments across the UK – would result in much greater frequency of their use by specified authorities. Could the increased regularity of developments stifled by these disputes force authorities to take this affirmative action at an early stage to mitigate these risks?

There remain many questions about how these two cases will unfold in the courts. Nonetheless, given the advanced state of modern measurement technology and the scale of modern city growth, fewer injunctions and greater guidance for measuring light look set to offer more support to developers in negotiating and resolving issues, with a court action only as a last resort measure.