Virtual building surveys: 6 things you need to know

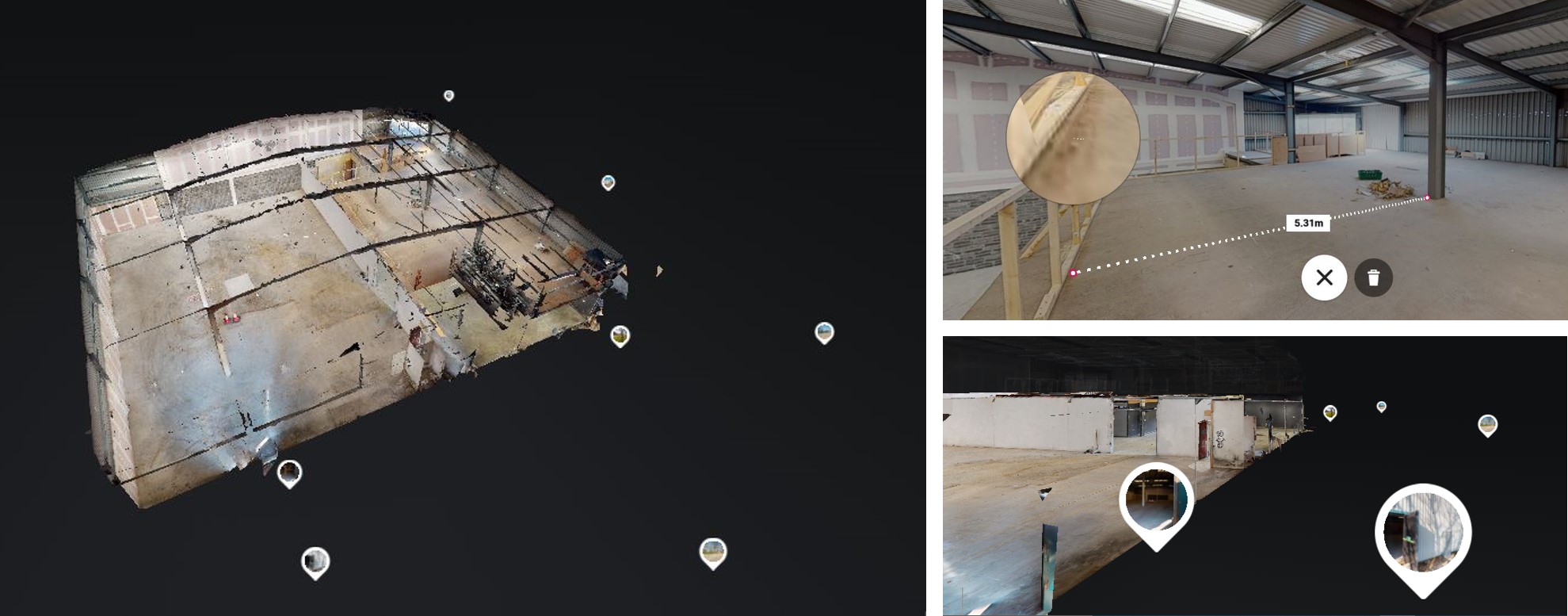

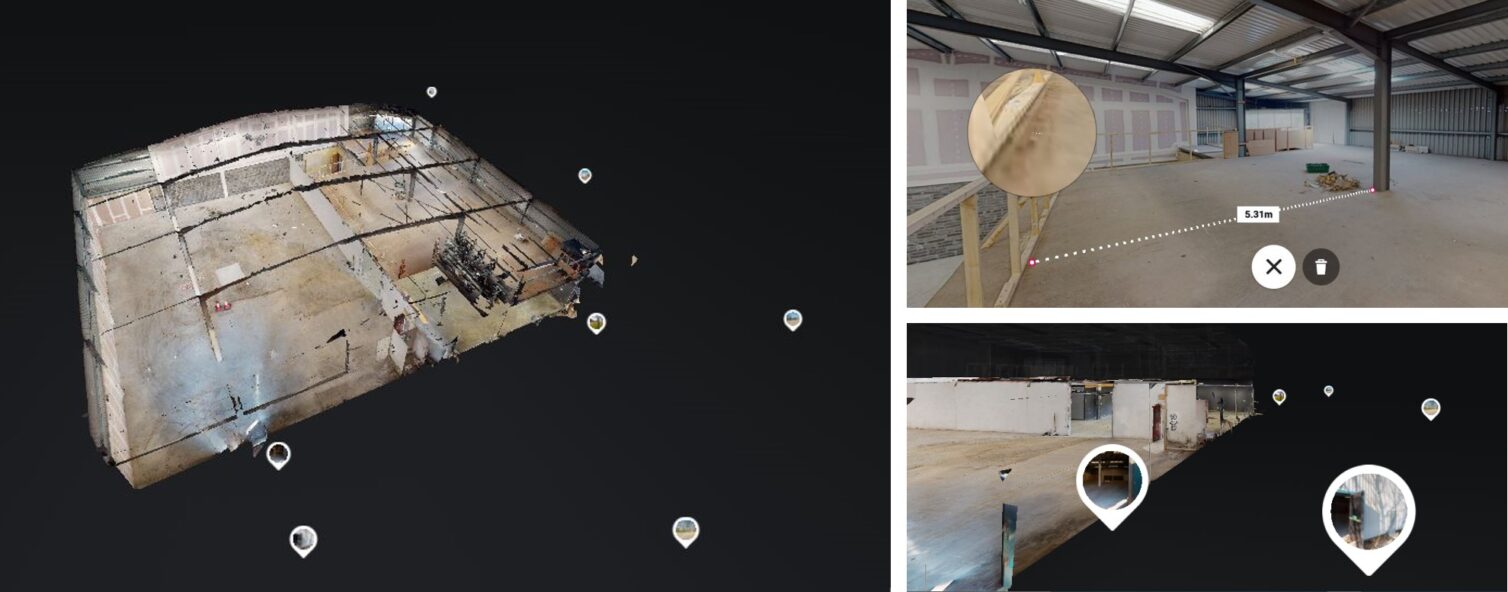

High quality visualisations produced by virtual building surveys are a powerful tool for investors, occupiers and other project stakeholders. We use them to save time when reviewing multiple buildings’ worth of information, or to communicate complex issues to non-technical specialists.

Here, we highlight the potential and limitations of the technology.

Virtual building surveys can have many applications across a building portfolio and construction projects. For instance, Technical Due Diligence (TDD), Dilapidations, Neighbourly Matters, Rights of Light and Project Management can all be enhanced by virtual surveying capabilities.

If you’ve never seen the output of a virtual survey before, we’ve mocked one up using our Bristol office. Give it a try by clicking here.

For all its uses and increasing market familiarity with the technology, the simple facts can be unclear.

Who needs it? How does it work? And is the cost worth it?

As with all innovation, we want to help our clients understand where technology can be leveraged across the building lifecycle – and where its limits lie!

Here are six things you need to know about virtual surveying:

1. Virtual surveys can save time and money

The great advantage of virtual surveying is the speed of information sharing. When investors, lawyers, asset managers and other stakeholders are required to visit sites and inspect details in person, the time and financial costs can mount.

Our high-quality visualisations are delivered along with a surveyor’s report within days of an inspection, providing all the necessary information for decisions to be made more swiftly.

2. Virtual surveys are easy to access and navigate

The surveyor completes the imaging process as part of their complete physical survey. Then the client receives a link to access the visualisation within a matter of days. That can be opened on any device from anywhere with an internet connection, with relatively little data load as the visualisation is hosted remotely. The experience is just like Google Street View – simple, flexible and highly informative.

3. Production is cost-effective and scalable

Imaging costs are a fraction of your building surveying fees, and these scale based on time spent taking the images. These aren’t tied to cost per square foot, but factors such as quantity of buildings or large, complex sites will take more time to photograph.

These rates are easily offset by savings on the resource required for investor clients, asset managers, project teams or lawyers to travel to the site physically. The larger the set of stakeholders who will be involved in seeing the building or acting on some aspect of the investigation, the more effective that small investment will be.

4. Virtual surveys reduce the need for (and risks of) travel

We face a long period of uncertainty about international travel and even some domestic trips might be disrupted in the event of local lockdowns. Virtual surveys can help off-set the risks of travel disruption for building transactions or other time-sensitive projects by relaying information quickly and accurately.

5. They can contribute to a powerful building record

Recording the building layout, fit-out and condition accurately can enhance Schedules of Condition reports. With a detailed visualisation and the surveyors’ report, occupiers and landlords can be certain of the state of a property at lease start and have a clear comparison with its condition at lease end.

Comparing a more up to date inspection to these previously recorded visualisations could make the dilapidations process more clear-cut for all parties.

6. There is no replacement for a full physical survey

The biggest misconception of virtual surveying is that surveyors or clients can make decisions solely from the visualisations it produces. This is not the case because physical investigation is a major component of any thorough survey.

For instance, we may need to scrape off paint to understand the material beneath it, take core samples of cladding or open up plant machinery to see its condition. Technology is some way off delivering that level of insight, and historic visualisations can miss out on recent unauthorised works, material deterioration and other deviations in the building.

Get in touch

Would you like to discuss the possibilities for virtual surveying across your portfolio? We’re happy to share our experiences and insights with you to understand how the technology could help you.